Photo: The Royal Mint

February 15 2021 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the United Kingdom’s switch to using decimal currency, and researcher Andy Cook has looked into this often-overlooked historical event for his PhD with the University of Huddersfield.

The move from the ancient system of £sd coinage to 100p to £1 was controversial, considered by some to be a sign of the UK’s receding importance on the world stage and even as the beginning of the tumultuous relationship with Europe that ultimately led to Brexit.

But as a result of extensive analysis of a quiet backwater of recent history, Andy argues that the move towards decimalisation had little to do with Europe and in fact was a traditional British compromise.

“It was an event that I remember from my youth, but I found that for such a significant decision that affected everybody in the UK, decimalisation is something that is not covered in much depth,” says Andy.

“It was the big news story in my teens. I mean, they changed the money! I wondered if anyone had done much about it, so I read around what people say about this period and what people have said recently about Brexit.

Commonwealth and not Europe a major factor

“Some see it as a harbinger of Europeanisation, leading up to the entry of the UK into the EU and ultimately the reaction to that process resulting in Brexit. My research shows that European considerations played virtually no part in that decision. There is no mention of Europe or the EEC in the original Halsbury Report that paved the way to decimalisation.”

Photo courtesy of The Royal Mint and the Royal Mint Museum

Photo courtesy of The Royal Mint and the Royal Mint MuseumOn the other hand, the Commonwealth was influential in the move to decimal currency, with South Africa, Australia and New Zealand all committing to decimalisation in the 1960s while Conservative and Labour governments in the UK wavered over whether to move in the same direction.

One option for the British currency was for it to be revalued in alignment with European counterparts like the Franc and the Deutschmark, which were around a tenth of the value of sterling. This was never considered seriously in Britain as it was seen as damaging to British prestige globally.

An exchange between Labour chancellor James Callaghan and BBC’s Graham Turner, available on YouTube, when decimalisation was announced in 1966 underlined the approach:

Callaghan: Speaking for myself I think there’s a lot to be said for the pound. Every one of us in Britain is familiar with it, we know what it stands for, abroad they know what it stands for.

Turner: Why have you decided not to use the word ‘cent’?

Callaghan: Oh, I much prefer ‘penny’, why should we go American – penny is a good, it is indeed the oldest coin in Britain, it was originally a silver coin. I see no reason why we should adopt ‘cent’, it’s a miserable sounding word by comparison with penny.

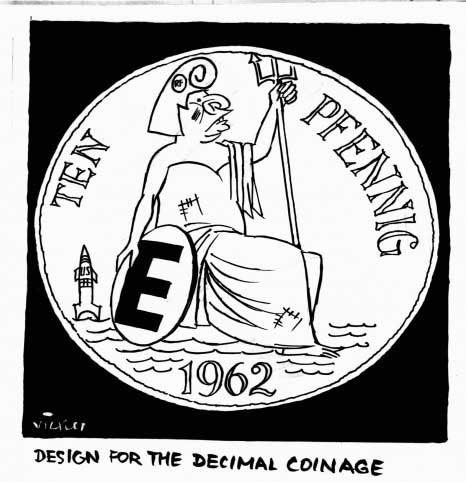

A cartoon by Vicky from the Evening Standard reflected how the move to decimalisation was seen to be a sign of Britain's waning influence on the world stage

A cartoon by Vicky from the Evening Standard reflected how the move to decimalisation was seen to be a sign of Britain's waning influence on the world stagePolitical and financial wrangles

To understand the development of the new currency, Andy looked at several aspects, “like the way it was managed politically, the lead up to it and how it played up the modernisation agenda – the attempt to arrest a period of British decline”.

“I looked at the influence of pressure groups and I found that consumers and retailers, who might have been concerned about currency reform, wanted to follow the lead of Australia and New Zealand in basing the new currency on a unit equal to 10 shillings, or half a pound.

“However, the City and the Bank of England were implacably opposed to any reduction in the value of the major unit, and they decisively influenced the government, playing into the inherent conservative instincts of Harold Wilson’s Labour government.”

Irish angle still relevant in 2021

The UK’s relationship with the Republic of Ireland was another significant element of decimalisation, and is an area of interest for Andy following his MA thesis, which looked at the last days of the Northern Ireland Labour Party in the same era.

He adds that, “Although Ireland eventually decimalised on the same date and on the same basis as the UK, the Irish government delayed their decision for two years, while they gave serious consideration to aligning their currency to that of the main European currencies. This to some extent presaged future developments in relationships between Ireland, the UK and Europe – clearly an issue with huge resonance in the present day.

“I visited the National Archive at Kew, and it was so helpful to be able to access old newspapers from the University, but I also accessed the national archives in Dublin for the Irish angle.”

Thesis could be basis for a book

Now retired after working in finance and then teaching in further education, Andy is keen to expand his thesis into a book. COVID-19 put paid to a visit to New Zealand last October where he was due to speak to the Royal New Zealand Numismatic Society, but he was able to present his research at their annual conference via Zoom. Since then a contact from the RNZNS as well as Professor Barry Doyle at Huddersfield have given him ideas for further writing.

Prof Doyle, who supervised Andy’s PhD, said, “This is a really original study that explores a topic overlooked by two generations of historians. The thesis was highly commended by the examiners who were particularly impressed with the way it showed the influence of both the Commonwealth and the Republic of Ireland, on the shaping of Britain’s currency reform.

“I’m looking forward to seeing Andy’s work in book form – it will make a huge contribution to our understanding of the modernisation of the British economy.”