Dr Mike Sanders’s talk at the 2018 Luddite Memorial Lecture examined the life and sermonising of ardent social reformer The Rev’d Joseph Rayner Stephens

IN the 19th century, English working class radicals drew on Scripture as much as politics. The close links between rebellion and religion were the theme of the 2018 Luddite Memorial Lecture at the University of Huddersfield.

It included a detailed analysis of the life and sermonising of The Rev’d Joseph Rayner Stephens – who went as far as arguing that if wages were too low then the Commandment “Thou Shalt Not Steal” no longer applied – and there was also an examination of the Democratic Chapels and the special compiled hymn books of the Chartist movement, which agitated for electoral reform and came close to violent insurrection.

“This close relationship between religion and politics is something that those of us used to a rather more secular society might find both unfamiliar and perhaps a little disconcerting,” said the lecturer, Dr Mike Sanders, of the University of Manchester.

He opened with examples of how religion was inseparable from politics and protest at the period. For example, when Luddites stood on the scaffold at York Castle in 1813, they joined together in the hymn “Behold the Saviour of Mankind” before their executions.

At the core of Dr Sanders’s lecture – titled Revolutionary Sermons, Democratic Chapels and Rebellious Hymnals: Religion in the Chartist Movement – was his exploration of J.R. Stephens, a former Methodist minister whose violent speeches and sermons led to his arrest for sedition and an 18-month jail term. He was based in the Lancashire town of Ashton-under-Lyne – a hotbed of Chartism.

Between his arrest in 1838 and his trial a year later, Stephens was on bail and delivered a series of 13 sermons that were published as The Political Preacher and The Political Pulpit.

“He presents political action as the necessary outcome of Christian faith and uses Biblical analogies to explain and analyse the economic, social and political condition of the working classes,” said Dr Sanders.

He explored Stephens’s use of Scripture to create his vision of a just social order. For example, the plight of the industrial workers of the North of England in 1830s was compared unfavourably to that of the Israelites in Egypt in the Book of Exodus, while Genesis provided arguments that working men were entitled to wages that would provide a pleasant life for them and their families.

“The affirmation of a right to reasonable comfort must have sounded pleasantly in the ears of those who received endless lectures on the supposed iron laws of economics which meant that wages must inevitably tend towards the level of subsistence,” said Dr Sanders.

“Stephens goes further still and argues that in a society where labour does not guarantee domestic security, then the commandment against theft becomes void.”

The preacher believed that Britain had become a hopelessly corrupt society and was therefore ripe for destruction by a wrathful God, and he also used martial imagery in his sermons, suggesting that violent confrontation between oppressors and oppressed was inevitable – this at a time when some Chartists were contemplating the use of physical force.

But although he coined the slogan “For children and wife we’ll water the knife”, Stephens then seemed to pull back from advocating violence, suggesting that the working classes should be more patient in awaiting deliverance. Dr Sanders described this as a “fatal ambivalence” in Stephens’s preaching.

“He insists that oppression must end and affirms the right of armed resistance but also insists that the time for fighting, though close, has not yet arrived.

“This might be seen as attempt to restrain his supporters from a potentially disastrous course of action or more cynically as his attempt to row back from his earlier invocations of violent uprising while still trying to maintain the favour of the crowd.”

Dr Sanders went on to describe his ongoing research into the network of Democratic Chapels established by the Chartists and also the contents and the language of the movement’s hymn books, of which a fragile example survives in Todmorden. Hymns had titles such as God Will Avenge Oppression and Spread The Charter Through The Land.

Dr Sanders also noted that Chartist hymns made little mention of the afterlife and avoided the first person pronouns that were common in conventional 19th century hymns, suggesting that they were more concerned with creating a collective religion than individual religious experiences.

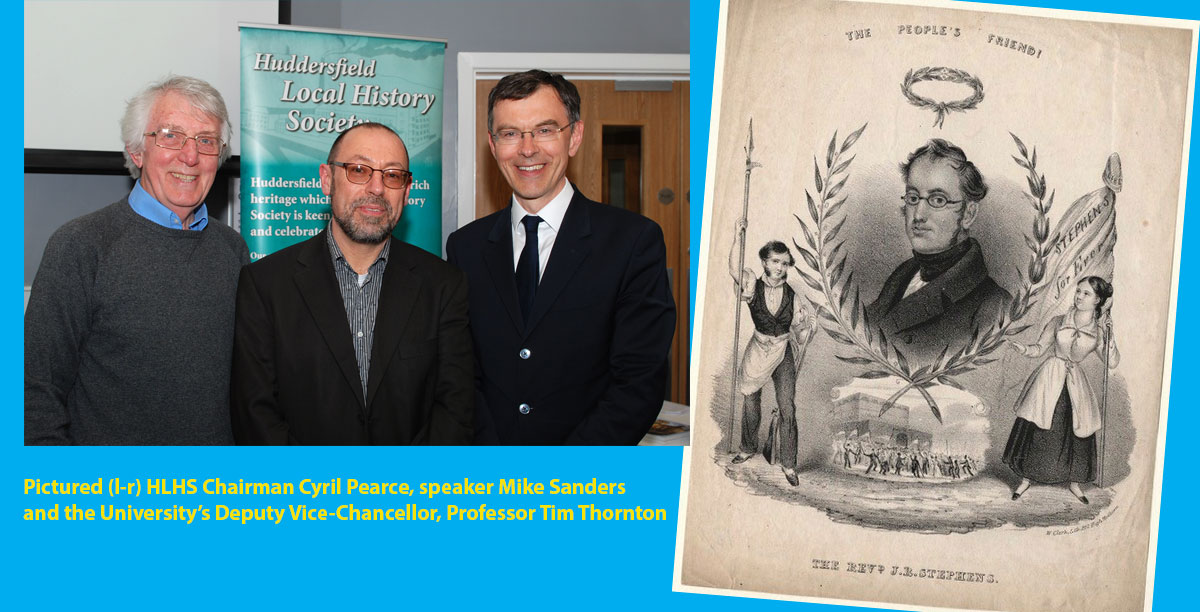

The lecture was the fifth in an annual series organised jointly by the University of Huddersfield and Huddersfield Local History Society. Dr Sanders was introduced by the Deputy Vice-Chancellor of the University, Professor Tim Thornton, and thanked by Cyril Pearce, who is Chair of the Society. He also invited questions from the audience that enabled Dr Sanders to offer more thoughts on the beliefs of The Rev’d Joseph Rayner Stephens.

More News

Educating migrant children in 1960s/70s Yorkshire

Joe Hopkinson wins the Royal Historical Society Public History Prize for his text/documentary on the controversial approaches used

The autobiographical writing of Lady Anne Clifford

Professor Jessica Malay’s new book of the lady described as the “Queen of the North” is launched at Skipton Castle

Yorkshire – A lyrical history of the Great County

Richard Morris’s book, Yorkshire, is already earning critical and media interest