New research into ancient DNA sheds light on key phase in European prehistory

Researchers at the University of Huddersfield have used ancient DNA to reveal that hunter-gatherers in one part of Europe survived for thousands of years longer than anywhere else on the continent – and have uncovered the pivotal role of women in the process.

The research was carried out as part of an international network of geneticists and archaeologists led by David Reich at Harvard University, and is published in the leading scientific journal, Nature.

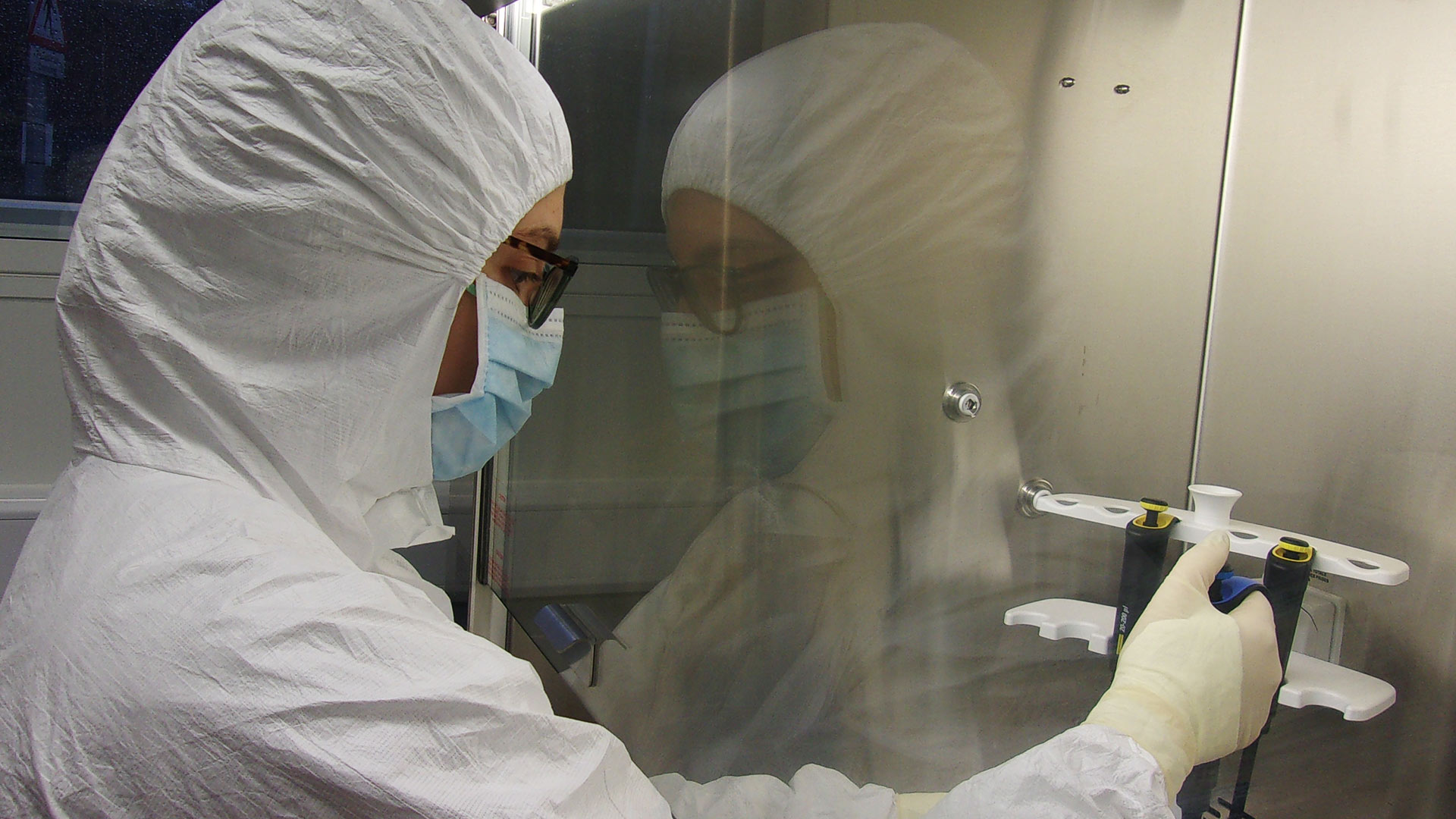

The work at the University of Huddersfield was carried out by research student Alessandro Fichera and post-doctoral fellow Dr Francesca Gandini, under the supervision of Dr Maria Pala, Professor Martin B. Richards, and Dr Ceiridwen Edwards, members of the Archaeogenetics Research Group within the School of Applied Sciences.

The research was funded as part of a Doctoral Scholarship scheme awarded by the Leverhulme Trust to Professor Richards and Dr Pala. The group collaborated closely with palaeoecologist Professor John Stewart at Bournemouth University and archaeologists at the Université de Liège in Belgium, who excavated and managed the ancient human samples.

The study analysed complete human genomes from individuals who lived across a region that encompasses modern-day Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands, between 8500 and 1700 BCE.

This was a particularly crucial phase in European prehistory when a series of major population and cultural shifts shaped the genetic composition of modern Europeans. Before national borders existed, people moved freely across large distances. In Europe, these movements involved the arrival of genetically distinct populations that mixed and therefore introduced not only new genetic components, but also new languages, cultures, and ways of life.

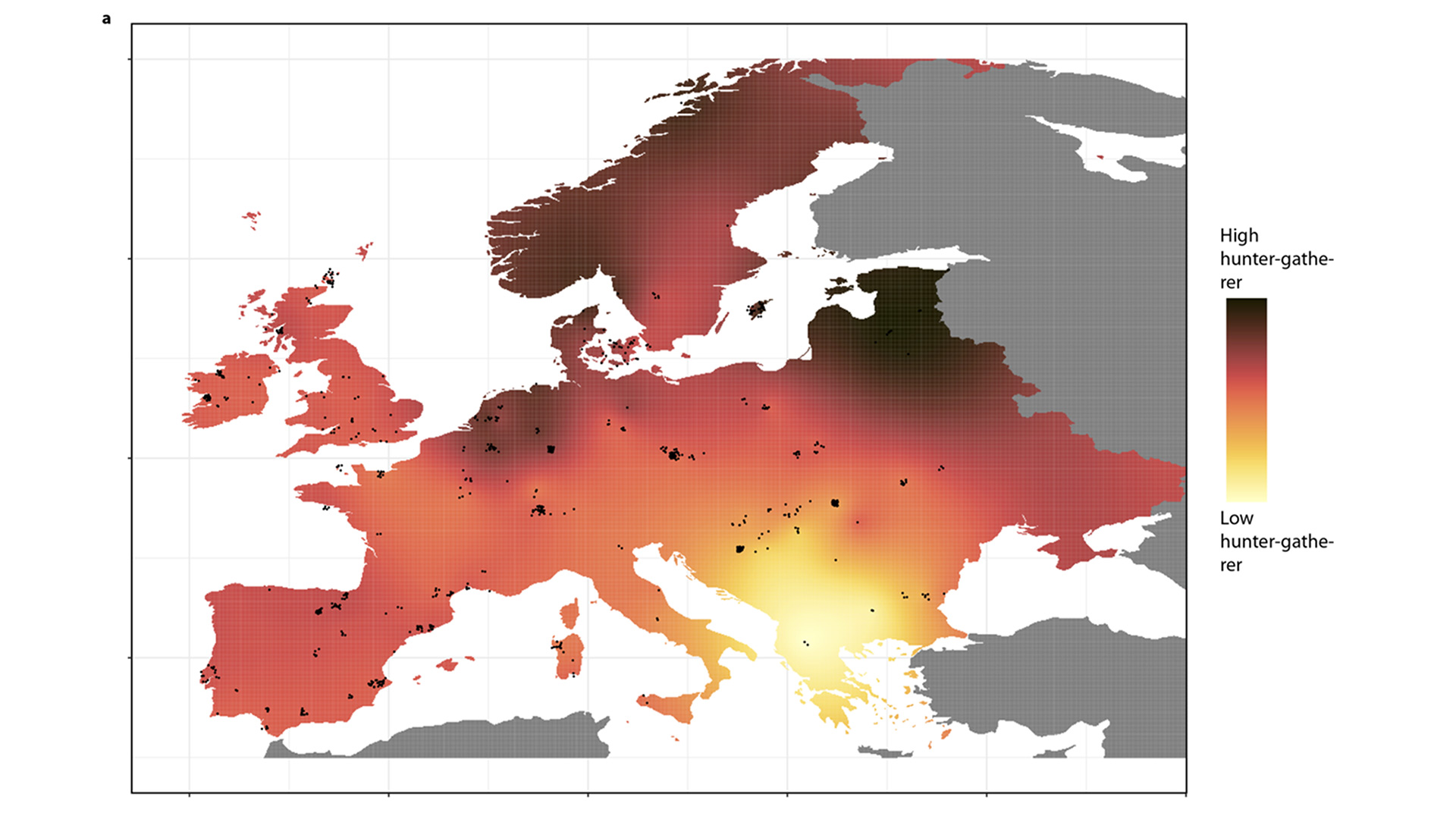

The impact of these changes was so profound and expansive that virtually all modern-day European populations carry evidence of three ancestral components: a hunter-gatherer component, a Neolithic component brought by the first farmers from the Near East, and a third component associated with pastoralists from Russia.

This latest research reveals that the arrival of farming in the area in question, around ~4500 BCE, did not result in anything like the major shift in genetic composition that took place across the rest of Europe. Instead, it involved the uneven acquisition of farming-related practices by local hunter-gatherer communities with only minimal genetic input from the incoming farmers.

Strikingly, genomic data from the study suggest that this farmer influx was mostly from women marrying into the local hunter-gatherer communities, bringing with them their know-how as well as their genes. This pattern was limited to the riverine wetlands and coastal areas across the region. The wealth of natural resources seems to have allowed the local people to selectively embrace some aspects of farming while also preserving many hunter-gatherer practices, and therefore genes.

The high levels of hunter-gatherer ancestry persisted across the region (modern-day Belgium and the Netherlands) until the end of the Neolithic, around 2500 BCE, when new people spread across Europe. The new incomers this time arrived and mixed fully with local communities, so that the genomic trajectory of the area finally realigned with the neighbouring regions.

Professor Stewart commented: "We expected a clear change between the older hunter-gatherer populations and the newer agriculturalists, but apparently in the lowlands and along the rivers of the Netherlands and Belgium, the change was less immediate. It's like a Waterworld where time stood still."

Dr Pala said: “Ancient DNA studies often bring to light unexpected pages of our past. We might anticipate finding the unexpected when analysing samples from unexplored or peripheral regions of the globe. But here we are looking at the heartland of Europe, making these results even more striking. It’s a testament to the power of ancient DNA studies that findings like these can still surprise us.”

She added: “This study has also brought to light the crucial role played by women in the transmission of knowledge from the incoming farming communities to the local hunter-gatherers. Thanks to ancient DNA studies, we can not only uncover the past but also give voice to the invaluable but often overlooked role played by women in shaping human evolution.”

The work is published in Nature journal here.