Huddersfield archaeologists help to reveal Namibian genocide grave sites

William Mitchell is pictured carefully excavating a grave that has been damaged and is gradually being eroded, in the presence of Ovaherero and Nama tribespeople.

Researchers from the University of Huddersfield’s Centre of Archaeology have travelled to Namibia to help uncover more evidence of atrocities from what has been called “the first genocide of the 20th Century”.

Tens of thousands of peoples from the Ovaherero and Nama tribes were killed during Germany’s occupation of the country, then called German Southwest Africa, between 1904 and 1908.

The Centre’s Kevin Colls and William Mitchell visited a cemetery in the coastal town of Swakopmund that is known to contain the remains of thousands of slave workers in marked graves.

Next stage in long-term project

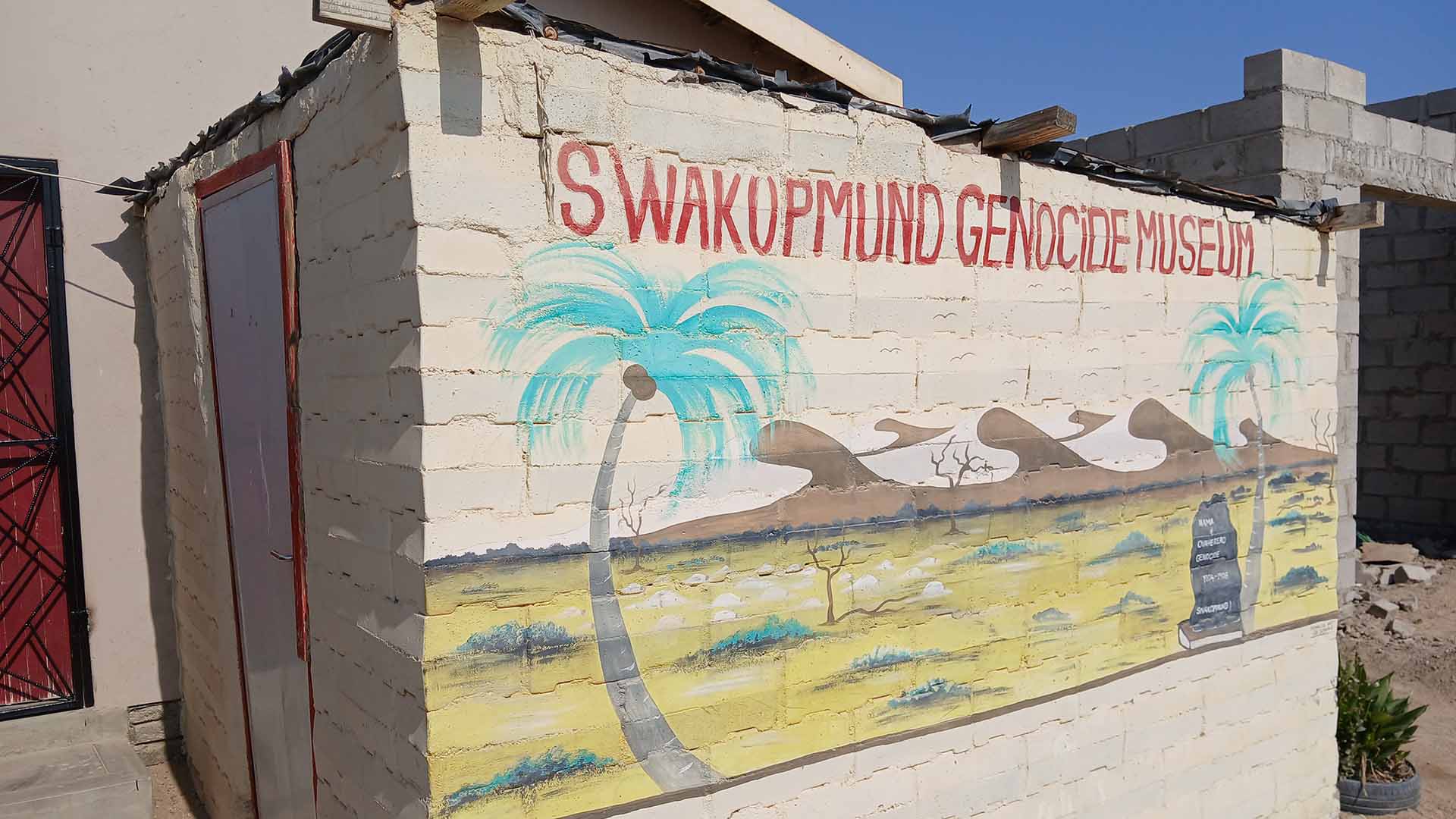

Kevin and William worked, alongside members of the Ovaherero and Nama communities and in partnership with Forensic Architecture from Goldsmith’s, University of London and Berlin-based Forensis. They used Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) and other techniques to discover the extent of hitherto unknown single and mass graves. They have also secured funding from the University of Huddersfield’s Impact Acceleration Account to help Laidlaw Peringanda, the curator of the Swakopmund Genocide Museum, redevelop his exhibition.

"The cemetery is on the edge of the town, with the Namib desert as a backdrop," says Kevin. "You see small sand mounds for as far as the eye can see, and each one of these mounds is a grave of a slave worker who lost their life whilst working for the German occupiers in brutal conditions.

"This is a continuation of an existing project aimed to study the areas withing the cemetery where there were no mounds in an attempt to understand if burials exist here. Many sand mounds have eroded away or been destroyed”.

On a previous visit, the team noted that some graves are so eroded that the edges of small wooden coffins or caskets are visible at ground level. Many were close to parts of the cemetery that is used as a thoroughfare for large vehicles.

'It was intense and emotional'

Another key priority of the project was to forensically excavate one grave in the presence of both the Ovaherero and Nama descendants. This was completed with permission from the Namibia Heritage Council (NHC), the National Commission on Research, Science and Technology (NCRST) and the Swakopmund Municipality.

"This was a vital part of the project, as it was the first excavation its kind and the first time we had descendants from both tribes on site to work with us,” Kevin adds. “They completed tribal rituals on the site, as both remembrance to their ancestors and to this specific individual whose grave was the focus of the work.

"It was intense and emotional, and when we had performed our forensic excavation, we could see that there was a body in the coffin and that their remains were only 0.15cm to 0.20cm beneath the surface. The human remains were not moved, and once detailed recording was completed, we backfilled the grave with the sand that was earlier removed. We then transported new sand from around the perimeter of the cemetery to form a new mound over the grave.

"The way it was described to me was that with the coffin revealing itself was the spirit of that person wanting to be known. It was extremely thought-provoking. This is one grave of thousands. They are all susceptible to erosion by the wind either off the sea or the desert, and some areas of this cemetery are under threat from building work.

"There is a small team of volunteers who maintain the site, and they are pleased that there is interest in the preserving the graves with all the potential threats to them, either from nature or man."

The Centre is also helping Laidlaw Peringanda to upgrade his museum. It is currently housed in a small extension to his own house and has been described by the Economist media outlet as “the smallest and yet possibly to most important museum in Africa”.

"Laidlaw is an activist and educator. He gets visitors, despite the museum's size, but the genocide is often ignored in public consciousness. So it's very important that we help him and the other volunteers get the story out to even more people."

The next stage of the project is to complete a comprehensive report, including detailed plans showing the location of burials within the cemetery without marked sand mounds and to work on the new exhibition ready for a launch later in 2025. Further seasons of fieldwork will take place next year and beyond, and several academic papers are in the pipeline which highlight this important project.